News Story

MC2 Experts Rank Nations' Vulnerability to Cyberattack

Reading panicky news stories about the perils of opening the wrong email, or frightening statistics on the prevalence of cyberattacks, you could get the idea that the United States is the No. 1 target of malicious hackers worldwide.

That may be conventional wisdom, but it’s wrong, UMD researchers argue in a recent book, “The Global Cybervulnerability Report.”

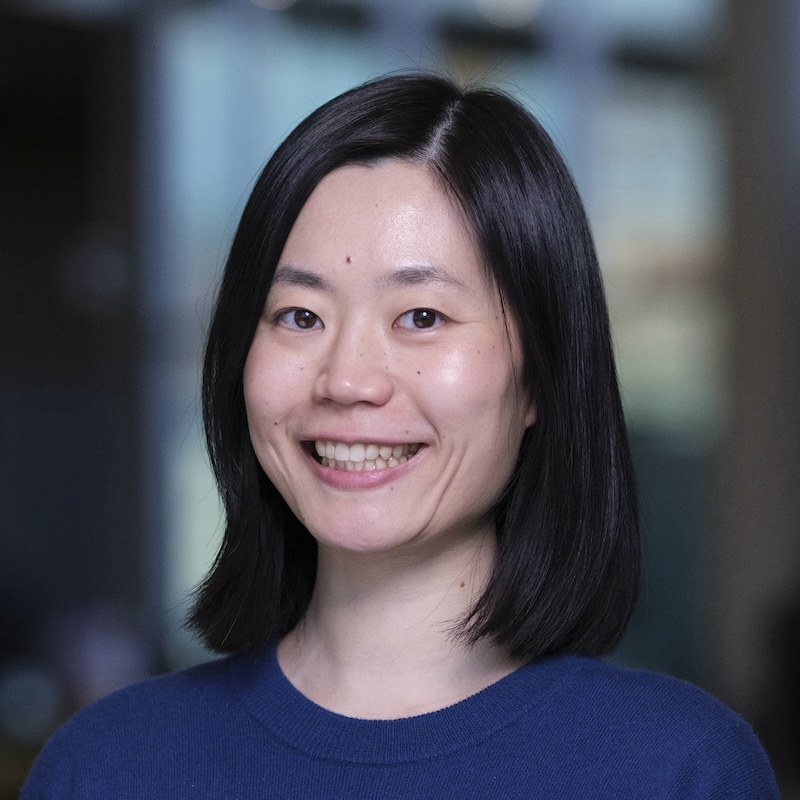

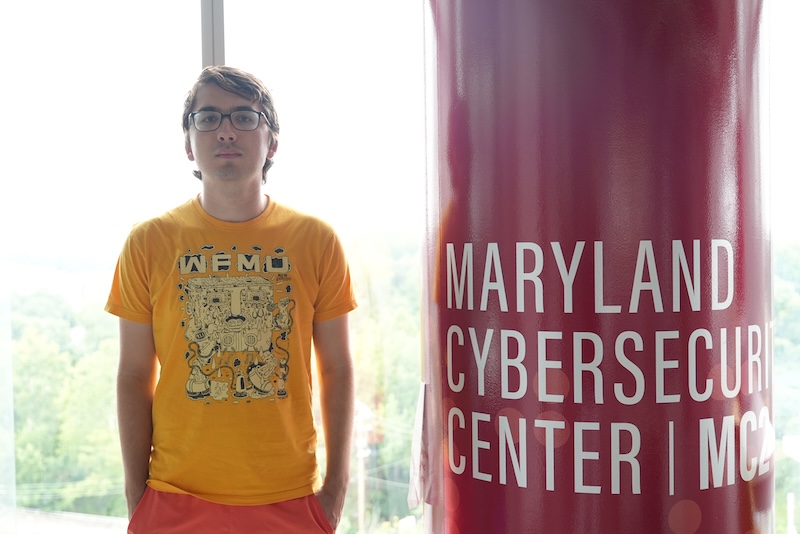

Lead author V.S. Subrahmanian, a computer science professor with an appointment in UMD’s Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS) and the Maryland Cybersecurity Center (MC2), used data provided by the computer-security firm Symantec to track how often individual computers are targeted in various countries. His collablorators include MC2 faculty member Tudor Dumitras, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering.

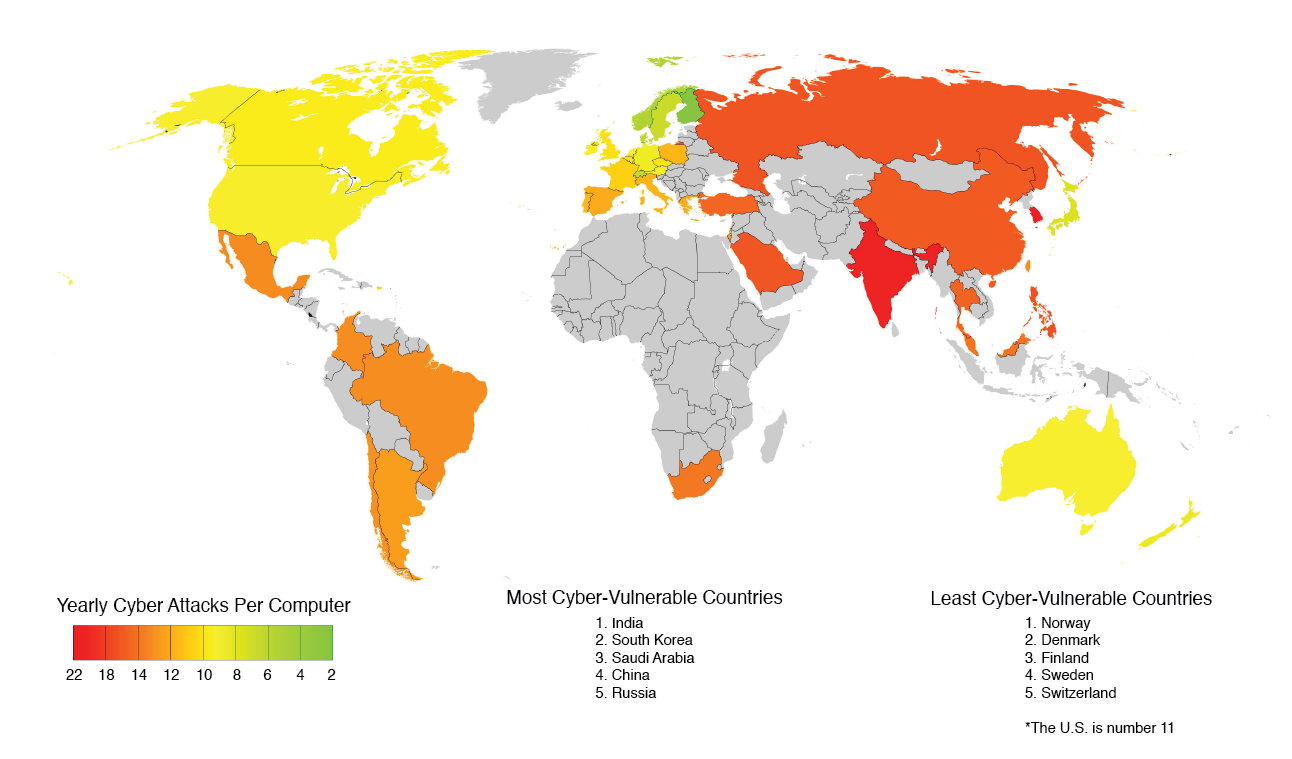

What they found, analyzing over 20 billion reports generated by more than 4 million computers (mainly personal and business machines) protected by Symantec products in 44 nations, was that the United States and its Northern and Western European allies are relatively safe. Overall, Scandinavian countries lead the pack in terms of their vulnerability to cyberattack.

Meanwhile, some of the world’s most dynamic developing economies, including India and China, were at or near the bottom. Russia, a country often viewed as a leading exporter of cyber mayhem, is also among the most vulnerable—perhaps, Subrahmanian says, because mounting an effective offensive cyber campaign is currently far cheaper and easier than defending against one.

Wealth appears to explain much of the difference, he says. Richer countries, where computer users have more money to spend on cyberdefense, generally do far better than poorer ones. (Going against the trend was relatively well-off South Korea, thanks to constant targeting by its aggressive northern neighbor.)

“The nature of the threat we face is just like those of other countries with our GDP,” he says, with one exception. American computer users seem to be uniquely vulnerable to what the book calls “misleading software”—usually fake antivirus or adware-removing programs designed to steal data.

“Despite being one of the safest countries,” Subrahmanian says, “we’re still vulnerable and there is a great need to defend ourselves both as institutions and as individuals.”